My previous post about the political orientation of fascists got a response from Jonah Goldberg, the author of Liberal Fascism. This is my brief response to his.

Goldberg assumes that I was criticising his book, which I was not. That’s my fault. I should have clarified that I was not commenting on his book at all, because I have never read it. I was reacting to the general meme that fascists were left-wingers or socialists — which one hears quite frequently these days. I suppose that was inevitable, given the longstanding promiscuous use of the epithet ‘fascist’ by the left.

(1)

A theme common to Goldberg, the people at his comments section, and many who have tweeted at me is that fascists should be judged from a classical liberal or a Hayekian perspective. I agree that’s a possible and valid way of looking at things — if you’re interested in an ahistorical ethical or ideological evaluation of fascist economics. Or if you’re interested in characterising a figure from history in terms of the current definitions of left and right.

But, historically, ‘pro-business’ or ‘pro-property’ fits the definition of the right in politics much better than ‘laissez-faire’. Businesses everywhere and always want pro-business policies — not laissez-faire, unless that happens to be consistent with pro-business at that point in history.

For example, when tariffs were considered beneficial for business, the pro-business party in the USA supported them during the 19th century, and the more populist party wanted to reduce or eliminate them. It was the same in the UK: the liberals advocated free trade while the conservatives wanted protection. In 1901-2, the Tories sought to abandon free trade, but the liberals waged a successful populist campaign to keep it.

The common thread to the right in history is not laissez-faire, but the tendency to support business or property. The common thread to the left is to redistribute income and property.

(2)

In my previous post I quoted at length from Buchheim & Scherner, which documents that the Nazis, at least in peace time, respected the private property rights of industrialists. State-industry relations were governed by contract and negotiation, not by compulsion and diktat. This line of reasoning was neglected by Goldberg, who in the comments section of his own post had this to say :

The economy was arranged in ways that benefitted the state. Industries that resisted the State were punished (as with the steel industry). Industries that complied with the State were rewarded (as with the chemical industry).

The punishment of the steel & iron industry was quite exceptional. Even then, according to Buchheim & Scherner,

An obligation to serve a specific demand hardly existed for the majority of firms. That also applied to orders from state agencies. Firms could, in principle, refuse to accept them. One of the rare exceptions to that rule occurred in late summer 1937 when the iron and steel industry was obliged to accept orders from the military and other privileged customers. This step, however, was qualified even by Hermann Göring as a “very strong” measure and after two months it was to be lifted automatically.31 Even in November 1941 Ernst Poensgen, director of the iron and steel industry group, still could frankly explain to the plenipotentiary for iron and steel rationing General Hermann von Hanneken that the members of his group were not prepared to accept further military orders; instead they wanted to serve orders from exporting companies, shipbuilding, and the Reichsbahn.32 Only in 1943 was an obligation to supply certain requirements reintroduced under the utmost exigencies of total war.

The above must be kept in my mind when it comes to the only substantive criticism I have seen of my post by Goldberg :

Yes, Nazis squelched independent labor unions. Yes, yes, Nazis repressed socialists and Communists. Fine, fine. You know who else treated independent labor unions roughly? You know who else repressed socialists and Communists? The Soviet Union. The Soviets surely killed and arrested more domestic socialists, starting with the Mensheviks, than the Nazis did. And how did labor unions fare in the Soviet Union? How were strikes treated? Let’s ask the survivors of the Novocherkassk massacre or the Kengir uprising. Were they not for all practical purposes folded up into paper-tiger fronts as extensions of the State?

Goldberg ignores that the state was the employer in the Soviet Union, whereas in Nazi Germany employers were mostly private. This makes all the difference in the world. By herding workers into the state labour union, the Nazi state directly intervened to weaken the bargaining power of labour against employers. And if you suppress wage growth when the economy itself is growing, then the capital share of income should rise. Unless the Nazis also fixed commensurately lower prices for output — which seems unlikely given Buchheim & Scherner — then labour repression by the Nazis must have redounded to the financial benefit of private employers. That’s starkly different from the Soviet situation.

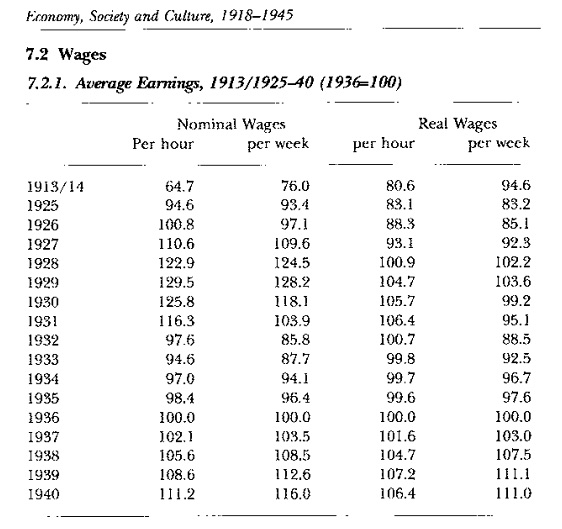

[Source of the table] Real hourly wages grew only by 6% or so between 1932 and 1939, with weekly earnings rising more than 25% as a result of working longer hours per week. Yet Germany’s GDP per capita rose by 60% between 1932 and 1939 [source]. Where did the rest of the growth go ? By default, it went to the capital share of national income, whose effect can be seen here :

[Source: Tooze 2006] The long-run rate of return on capital is 4-5% in industrial economies. So the leap in profitability for German business in the 1930s was pretty hefty. Much of this profitability did not show up in the income of the top decile; rather it showed up mostly in the top 1% :

[Source: Dell 2005]

[Source: Dell 2005]

So let’s consider another passage from Goldberg’s post :

So Pseudoerasmus (and many others) notes that the Nazis maintained (limited and often purely rhetorical) respect for private property! The Soviets didn’t! Therefore, the Nazis were not left-wing! Well, Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders believe in private property a good deal more than the Nazis did. Does that make them right-wingers?

I’ve heard of Bernie Saunders (the only socialist member of the US Congress), but I had to look up Elizabeth Warren. I can’t imagine their economic policy preferences would include increasing the profitability of the business sector or the income of the top 1% at a rate faster than that of workers… In fact I’m pretty sure they would prefer to invert that drastically.

Update/Addendum: Originally I could not find the measured factor shares of income for Germany in the 1930s, so I only posted the rate of return on capital. But now I’ve found it. According to Barkai, the labour or compensation share of German national income dropped by 5 points between 1932 and 1936. That’s quite drastic for such a short period ! Also see similar estimates for real wages & labour share from Braun but larger estimates for the drop in the labour share from Overy. Here’s a graphic from Schneider 2011 :

Update/Addendum 8 May 2015:

The combined votes for Socialists (SDP) & Communists (KPD) in German elections :

1932: <36%

1930: <40%

1928: <41%

1924: ~35%

There was remarkably little defection out of the left in general. Even more constant through thick and thin was the support for the Catholic Zentrum :

1932: ~12%

1930: >12%

1928: ~12%

1924: <14%

The quasi-separatist Bavarian People’s Party also always got around 3%. In other words, the Nazis went from 2.6% in 1928 to >37% in 1932 by pinching votes from the traditional non-socialist parties other than the Catholic Centre Party.

Update/Addendum 9 May 2015: The Great Depression spurred a small wave of nationalisations of private enterprises in the industrial countries, including Germany prior to 1932. But the Nazis reversed this trend. Enterprises privatised by the Nazis include: Germany’s largest banks controlling up to 40% of banking assets; the railways (which were one of the largest state-owned enterprises in the world); as well as ship-builders, shipping lines, public utilities, mining companies, and a steel works which was Germany’s second largest company. None of this was done with principle in mind, but with a view toward gaining support from industrialists. See “Against the Mainstream: Nazi privatisation in 1930s Germany“.

Update: This post got picked up by David Keohane of FT Alphaville.

Only Americans could take seriously the proposition that fascism was a left wing movement. That is probably a function of the minimal ideological variation that can be found within the American political spectrum. With the exception of the civil war, and possibly some of the nuttier fringes of the modern Republican party, the USA has never had a party that radically sought to reshape the State and create a New Man. America has basically been a one party state for most of its history.

For example, one characteristic of European left wing movements is the radical rejection of nationalism and patriotism in favour of internationalism. Americans tend to discount the “nationalist” part of the NSDAP as just normal – of course a political party will be nationalist, is there any other option? But that is (one) of its radical differences, and the reason for its solid placement at the extreme right of the spectrum.

Essentially, Americans look at politics with dogs’ eyes – they can only see three colours at best. And so socialist and fascist movements look indistinguishable to them. This is not necessarily a critique – a history so bland as to engender such an utter lack of political diversification is a great testament to the unprecedented peace and prosperity that Americans have enjoyed during much of their nation’s existence. But how can you explain the Reaction to a nation that has never had an aristocracy?

LikeLike

I like your comment, but I think it’s an Anglosphere phenomenon, not simply an American one.

LikeLike

We’ve had all these sorts of parties; they just never caught on. As you say, America had a labor shortage for most of the relevant history, and a very large class of small landowners, so the country was just too bourgeois to take much interest in it (though we did develop some fun and sort of bizarre populist movements out west). And internationalism has less appeal when you only have two immediate neighbors of any size, one of whom is culturally very similar to you, and a large immigrant population from which some sort of collective political identity needs to be created. Our anarchists, new internationalists, communists, etc were mostly immigrants, who had little success interesting the wider native society in the ideas, and then most of their children assimilated and lost interest themselves. Since we’re first-past-the-post, there’s no place for small parties to gain much of a foothold.

There’s also an argument to be made that internationalism gains in appeal in direct proportion to your nation’s relative decline as a world power. I don’t know if I believe that argument, but it seems vaguely plausible.

LikeLiked by 1 person

If politically-myopic Americans or Anglos are to be blamed for reducing fascism to a left-wing phenomenon, then explain the German historian Götz Aly’s recent book Why the Germans? Why the Jews? Envy, Race Hatred, and the Prehistory of the Holocaust? Because he takes the same position as those dog-eyed Americans, and not without reason.

Aly looks to the sources of Nazism. Where it arose. The background of those who became its leaders and filled its ranks. The early agendas of those who led it.

Most of the above is probably pretty well known to everyone commenting here. But Aly takes it further. He looks, for example, at the social backgrounds of the Nazis.

Although it’s not his main thesis, Aly goes on in this vein for some time. The Nazis were not Chamber of Commerce types worried about the effect of labor strikes on capitalists; they were very much interested in helping the German people they represented get ahead, and those German people were not anywhere near the top of the heap. Their main target in fulfilling that aim were not German capitalists, but the economically successful Jews. Hence, the “envy” in the title of Aly’s book.

Thus we have Hitler’s famous rhetorical question, ““How, as a socialist, can you not be an anti-Semite?”

I have nothing against Pseudoerasmus’s mode of analysis. It’s certainly one way to look at this question. But he sometimes argues as if the Nazis were as economically sophisticated as he is, as if they couldn’t help but be aware of the implications of their policies of wage suppression unaccompanied by profit suppression.

LikeLike

Pincher, your comments are invariably fascinating. When are you going to blog or tweet to spread some of the goodness?

LikeLike

Whyvert,

Thanks for the kind words, but I prefer to act as a parasite on the much heavier erudition of other bloggers who do the hard scholarship that make my brief comments appear to be sharper than they really are.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You realize that your approach is the exact opposite if the one espoused in the blog post? Our host is saying that to decide whether the fascists were right or left, we should look at what those terms meant in that time and place, while you’re saying that Americans may think that they have both right and left wing parties, but from your perspective as an outsider, you’re able to determine that they do not in fact have a genuine left.

Also, consider that perhaps the European political spectrum is also narrow, it’s just centered on a different spot from the American one, and perhaps as a result Europeans don’t properly understand the difference between the right in Europe and the right in America.

A third point: most Communist regimes have been, in practice, nationalist (and militarist). Does that mean they were actually on the extreme right?

LikeLike

Hitler was a socialist. Nazism began with state ownership of many industries including banking, steel, shipbuilding, transportation, etc. It began to return property to private hands later because it needed cash flow; its treasury was depleted during armaments buildup in the mid 30s.

Detail and citations as follows:

While early National Socialist programs nationalizated major industries, i.e. banking and steel, later there was reprivatization of some business, in particular between 1934-37 during increasing armaments buildup. Privatization was applied within a framework of increasing control of the state over the whole economy through regulation and political interference.

According to The Banker (1937, p. 114), increased expenditures after 1933/34 were basically taken up by armament programs. In August 1936 Hitler issued the “Four-Year Plan Memorandum” ordering Hermann Göring to have the German economy ready for war within four years.[47][48] The “Four-Year Plan” increased state intervention in the economy and siphoned off resources from the private sector for rearmament. These are the main policies that explain the evolution of public expenditure and some of the privitization. As early as in April 1934, The Economist reported that military expenditure was forcing the Minister of Finance to look for new resources. At that time, “Railway preference shares are to be sold to the extent of Rm. 224 millions. The Reich property, which is to be ‘liquidated’ …

The intense growth of governmental regulations on markets, which heavily restricted economic freedom, suggests that the rights inherent to private property were destroyed. As a result, privatization would be of no practical consequences since the state assumed full control of the economic system (e.g. Stolper, 1940, p. 207).

Guillebaud (1939, p. 55) stresses that the Nazi regime wanted to leave management and risk in business in the sphere of private enterprise, subject to the general direction of the government. Thus, “the State in fact divested itself of a great deal of its previous direct participation in industry….But at the same time state control, regulation and interference in the conduct of the economy affairs was enormously extended.” Guillebaud (1939, p. 219) felt that National Socialism was opposed to state management, and saw it as a “cardinal tenet of the Party that the economic order should be based on private initiative and enterprise (in the sense of private ownership of the means of production and the individual assumption of risks) though subject to guidance and control by state.” This can be seen as the basic rationale for privatization.

The Reich was strongly against free competition and regulation of the economy by market mechanisms (Barkai, 1990, p. 10). Hitler was an enemy of free market economies (Overy, 1994, p. 1). It is interesting to note two interviews in May and June 1931, in which Hitler explained his aims and plans to Richard Breiting, editor of the Leipziger Neueste Nachrichten, on condition of confidentiality (Calic, 1971, p. 11). With respect to his position with regard to private ownership, Hitler explained that “I want everyone to keep what he has earned subject to the principle that the good of the community takes priority over that of the individual. But the State should retain control; every owner should feel himself to be an agent of the State….The Third Reich will always retain the right to control property owners.” (Calic, 1971, p. 32-33).

Against the mainstream: Nazi privatization in 1930s Germany, p. 13-17

Also see Watson’s contemporary scholarship of the National Socialism:

http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/hitler-and-the-socialist-dream-1186455.html

“The State must act as the guardian of a millennial future in the face of which the wishes and the selfishness of the individual must appear as nothing and submit.” — Mein Kampf

LikeLike

When Hitler came to power, he moved to correct this hyperinflation while keeping his national socialist views front and center. The Nazi disbanded the Weimar unions and replacing them with the German Labor Front–which was comprised the National Socialist Factory Organization and the National Socialist Trade and Industry Organization. The labor contracts that were Weimar contracts were now DAF-honored contracts. The Nazi’s funded the DAF’s coffers with the Weimar unions’ stockpile of wealth (the existing unions were part of that inflation problem). One of the new unions’ most popular programs was the Strength through Joy (Kraft durch Freude, KdF)) program, which developed the KdF-wagen, that later became the Volkswagen, or People’s Car.

Hitler believed that socialism of the future would lie in “the community of the volk”, not in internationalism, as he claimed, and his task was to “convert the German volk to socialism without simply killing off the old individualists”, meaning the entrepreneurial and managerial classes left from the age of liberalism [a reference to classical liberalism]. They should be used, not destroyed. The state could control, after all, without owning, guided by a single party, the economy could be planned and directed without dispossessing the propertied classes. Hitler intent was to build socialism without civil war. As he described, his task was to “find and travel the road from individualism to socialism without revolution”.

LikeLike

Hitler’s own words from Mein Kampf:

“I think that I have already answered the first question adequately. In the present state of affairs I am convinced that we cannot possibly dispense with the trades unions. On the contrary, they are among the most important institutions in the economic life of the nation. Not only are they important in the sphere of social policy but also, and even more so, in the national political sphere. For when the great masses of a nation see their vital needs satisfied through a just trade unionist movement the stamina of the whole nation in its struggle for existence will be enormously reinforced thereby.

Before everything else, the trades unions are necessary as building stones for the future economic parliament, which will be made up of chambers representing the various professions and occupations.”

LikeLike

And here’s Hitler’s own words from his book, Mein Kampf:

“I think that I have already answered the first question adequately. In the present state of affairs I am convinced that we cannot possibly dispense with the trades unions. On the contrary, they are among the most important institutions in the economic life of the nation. Not only are they important in the sphere of social policy but also, and even more so, in the national political sphere. For when the great masses of a nation see their vital needs satisfied through a just trade unionist movement the stamina of the whole nation in its struggle for existence will be enormously reinforced thereby.

Before everything else, the trades unions are necessary as building stones for the future economic parliament, which will be made up of chambers representing the various professions and occupations.”

LikeLike

is that ROE before or after taxes? because: “The only major tax increase enacted between 1933 and the beginning of World War II to cover the spiraling deficit was in the corporate income tax, which had been introduced nationally in 1920 under the Weimar Republic. In four stages between August 1936 and July 1939, the base rate of that tax was doubled from 20 to 40 percent. The hike was aimed particularly at corporate enterprises that profited from rearmament, and the government increased the taxable base for enterprises by reducing the possibility of tax depreciation.”

and when looking at hourly wages as a source for income (wages that many millions wouldn’t have earned without the state funded infrastructure projects), you should also take the many welfare payments and handouts into account: “Family and child tax credits, marriage loans, and home-furnishing and child-education allowances were among the measures with which the state tried to relieve the financial burden on parents and encourage Germans to have more children.”

Talking about child benefits: “For many people, the regime’s aim of leveling out class distinctions was realized in the Hitler Youth, the National Labor Service, the major party organizations, and ultimately even in the Wehrmacht. The Nazis’ fondness for uniforms is today seen as a manifestation of its militarism. But uniforms, whether worn by schoolchildren or Boy Scouts or sports teams, are also a way of obscuring differences between the well-off and their less fortunate peers.”

Summer holidays for kids in the Hitler Youth was free of charge (including travel, food and lodging), also all education from preschool up to college.

And even when “the KWVO temporarily suspended extra pay for overtime and for night, Sunday, and holiday labor, the take-home income of working-class Germans decreased at the onset of the war, but employers were not the ones who profited: they were required to pay an equivalent sum to the state”; “bucking all wartime financial logic, the political leadership reinstituted overtime pay for nine- and ten-hour workdays in August 1940.”

also: “In 1941, for reasons similar to the ones motivating tax breaks for farmers, the government raised pensions. The 1941 pension reform also introduced mandatory health insurance. Previously, retirees had had to apply for state relief assistance or take out private insurance, which few of them did.”

“In spring 1943, the finance minister failed to push through a proposed 25 percent tax surcharge on lower-income workers, who thanks to the Nazis’ wealth redistribution policies were now comparatively well-off. Göring dismissed the surcharge proposal categorically, and Hitler declined to intervene”

A lot of the welfare measures the Nazis enacted, Austria and West Germany kept in place after the war by the then ruling socialist or socialist-conservative coalitions and we still have them today. So also for me, NSDAP was mostly a socialist (not marxist) party, very much looking like the SPD after http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Godesberg_Program.

(all quotes taken from: [Hitlers Volksstaat. English], Hitler’s beneficiaries: plunder, racial war, and the Nazi welfare state / Götz Aly; translated by Jefferson Chase, 2005, 2006)

LikeLike

btw., with Deutsche Reichsbahn (DB), it’s the other way round: since 1924, it was a private company in name only (Deutsche Reichsbahn Gesellschaft, 100% state owned), but the Nazis nationalized it in 1937, together with the also formerly nominally independent central bank, changing the name to DB and employing all workers directly at the goverment (Verbeamtung): http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deutsche_Reichsbahn; http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gesetz_zur_Neuregelung_der_Verh%C3%A4ltnisse_der_Reichsbank_und_der_Deutschen_Reichsbahn

The Nazis also nationalized all private railway operators in the countries they conquered between 1938 and 1943: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deutsche_Reichsbahn_%281920%E2%80%931945%29

LikeLike

(1) I don’t know whether the rate of return on capital in the chart above is before or after taxes. But the ROR chart has a dip between 1936 and 1939, so perhaps it is after-tax.

(2) The growth in Germany’s consumption per capita, as well as consumption output per capita, is quite consistent with the growth in real earnings.

LikeLike

It really is simple; Fascism takes the name from the ancient roman Fasces, an axe with sticks bound around it, symbolising “collectivism”. In my world collectivism is a broad word for socialism.

LikeLike

Then in your world, capitalists are socialists.

LikeLike

I one misunderstanding is that a lot of right-wingers, perhaps Goldberg included, don’t agree with your premise, “The common thread to the right in history is not laissez-faire, but the tendency to support business or property. The common thread to the left is to redistribute income and property.”

A different conception of the right-left spectrum would be, “The common thread to the right is to support traditional authority, the common thread to the left is to undermine traditional authority.” So yes, the original right, in the French National Convention, supported “property,” but that was because the aristocratic order derived its power from property ownership. That same right was NOT supportive of capitalism.

Another certainly right-wing, but not laissez-faire school of thought is Distributism: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Distributism. There are numerous others.

LikeLike

I agree with that, but (1) my first post referenced the importance of the attitude with respect to traditional elements of society; and (2) since Goldberg seemed to narrow his focus on political economy, in this post, I also narrowed in on political economy.

In the transition period from an agrarian to industrial economy, the poles of opposition would be agrarian/landed property versus urban/industry. I tried to cover that by saying “pro-business’ OR “pro-property”, and deliberately did not use the word “capitalism”.

LikeLike

I would have said neither left nor right. I think of fascism as an extreme of populism, itself a phenomenon more recognizable by its paranoid tinge (Hofstadter) than from any consistent set of political or economic policies.

I once saw/heard Fritz Stern of Columbia, responding to class question along these lines, shrug his shoulders and say of Fascists that they were “basically gangsters”. Certainly they were angry nativists, cynically and opportunistically eclectic, and perhaps truly sincere chiefly in their love and recommendation of violence. I haven’t read any fascist “writers” in a long time, or ever in detail, but little of their several ideologies made any sense to me in any context beyond the intent to prey upon a vacuum of legitimacy and mobilize an angry response out of economic desperation and political and cultural despair.

Once in power, of course, fascists had little choice but to become problem solvers of a sort and they had to make policy decisions beyond the scope of the next purge. The resultant policies were all over the place – as this debate verifies. In these policies I don’t doubt that the investigator can detect the common odor of the fascist “special sauce”, but I don’t believe that this stink has anything to do with a consistent or genuinely thought-through political or economic approach.

LikeLike

But you can say that about most political movements. Occasionally you have political leaders with a very clear policy agenda (e.g., Thatcher), but most others have vague ones and improvise. YET, as I pointed out in my previous post, there is a certain consistency amongst the diverse fascist states that actually existed in their behaviour toward capital and labour. Maybe I did not make clear enough; the issue is not of principled ideology, but interest groups and support bases.

LikeLike

To leave my rant and return to the “political economy” theme of this post, is it correct to say and, if so, is it significant that in both the ‘return on capital’ and the ‘top 1% share’ charts above, that the upturns seem to anticipate the political changes of 1933?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Fascism was left-wing ??? | Pseudoerasmus

I found it interesting and informative how pro-business the Nazis were in the 1930s, especially compared to the Popular Front in France or the New Deal in the US at the time. But what of the 1940s? Starting a world war cannot be considered pro-business. It suggests that in the end they had other, higher, priorities.

LikeLike

Is your “historical” viewpoint the most useful one? It’s very common to have, in a particular time and place, groups that are rivals or enemies and consider themselves quite different, whereas if one takes the outside perspective, one sees that they are all products of their time and have quite lot in common. (This also works geographically, as Hypnos points out in his comment on “the minimal ideological variation that can be found within the American political spectrum.”)

Another point- as I’m sure you realize, most people taking sides on this issue are less interested in determining whether fascists were right or left, as those terms were defined in the 1930’s, than in trolling the right/left nowadays by saying “you guys are fascists”; they want to know how fascism fits in to the current definitions of right and left.

LikeLike

I’m a little surprised Pincher and Tomato believe my point depends on fascist rank-and-file having “consistent or genuinely thought-through political or economic approach”. I thought I tried to depict, especially in the previous post, an emergent outcome of interest groups and traditional classes.

Pincher’s comments are sociological. I make no extrapolations about how the average Nazi party member felt, thought, or believed. It’s not clear how the preferences and predispositions of the rank-and-file ultimately translate into policy, especially in a totalitarian regime. I can only tell you about things like voting patterns in 1932, or policy outcomes in the rest of the 1930s.

I also think the social picture painted by Götz Aly, as quoted by Pincher, is a bit skewed. There are now thorough studies of the social base of Nazi voters and party members, including the occupational background of the membership by percent by year. The membership was more diverse than was once believed in the 1950s-70s, but it’s still arguably more than half traditional middle class.

LikeLike

If the Nazi leadership was informed by class analysis, but they viewed class struggle as mainly dealing with the Jewish problem, then the Nazi solution to that problem was both very Marxist and a consistent policy of theirs from the moment they took power until the moment they were defeated.

Götz Aly makes that argument. The Nazis believed in socialism, but they saw the main villain not as the industrialist or the landlord, but as the successful and enviable Jew. So for them class struggle was not, as in Stalin’s USSR, about wiping out classes like the kulaks or, as in Mao’s China, about working over the now-landless Chinese landlords in struggle sessions. It was about dispossessing and ultimately killing the Jews. That was the way to social equality for Germans.

I’m sure that makes for crude economic policy when you look at, say, how labor’s share of the economic pie fluctuated during Hitler’s regime, but the Nazis didn’t see class struggle that way. By taking away a German Jew’s job and giving it to another German, they were striking a blow for the common German man. By dispossessing Jews, they were hitting the mark right where they thought it would do the most good. When Vienna sent their many Jews packing, rents in the city went down dramatically. Another blow for the common German man !

How is this absurd practice not an “emergent outcome of interest groups and traditional classes”? You’re looking for evidence of sound economic policies that broadly benefited the German working class, and the Nazis thought they were implementing them. They just weren’t sound.

Of course the problem with this analysis is that the centrality of the Jewish problem to Nazi ideology doesn’t transfer out of Nazi Germany to other fascist states. But then the threads that connect Mussolini, Franco, and Hitler were never very many. Perhaps this is a result of what you describe as the relative newness of fascist thought at the time.

LikeLike

Pincher,

Haven’t many right-wing movements up to the present been comfortable distinguishing between the “deserving” rich/poor and the “undeserving” rich/poor? It seems to me quite consistent with at least a certain strain of right-wing thought to say that Aryan capitalists are fine, while Jewish capitalists are evil exploiters. This might take more work to flesh out, but I think a good first approximation of the difference between rightist and leftist populisms is that leftists critique elites on the basis of their functional role in the economic system, whereas rightists critique only certain elites on the basis of economically extraneous characteristics, like personal morality, religion, ethnicity, or race. In practice, this distinction might not be a hard and fast one (think of the Khmer Rouge extermination of the market-dominant Chinese minority in Cambodia, to pick just one example), but it’s there in theory, at least.

LikeLike

Pincher, your remarks are compelling, but….

(1) They are the Nazi version of “Mussolini’s 1919 platform” argument that we’ve had in the past, and which I’ve rejected for reasons you already know. Besides your narrative pertains to the “Strasserist” lineage of the NSDAP, which was sidelined at the Bamberg conference and then more or less explicitly crushed in 1934.

(2) The narrative you tell is definitely not the “emergent outcome of interest groups and traditional classes” approach I’ve taken, because it’s confined to the earliest lineage of the Nazis. Remember, before 1930, the NSDAP didn’t even have a million votes.

(3) There was no fusion of socialist thought and antisemitism. It’s certainly not there in Mein Kampf. It’s not new to observe that the Nazis had linked traditional socialism with internationalism and Jews, and they proposed to create a national community without Jews which would take care of any “capitalist exploitation” problem. But I think that odour of socialism is in the trappings rather than in the substance. It’s not that the Nazis saw the obstruction to social betterment and mobility of the lower classes as fundamentally embedded in capitalism (the socialist view), but in a kind of foreign domination that perverted class relations.

(4) I just read a good chunk of Götz Aly, which I find more conventional and less compelling than the Pincherian narrative.

In some of what I say about this I’m quite influenced by the classic Crisis of German Ideology.

LikeLike

Matt, what you’re saying is in the vein of many Sowellian observations about invidiously successful minorities (plus the “market dominant minorities” of Amy Chua). I think those are also consistent with Götz Aly.

LikeLike

PE,

But is resentment against MDMs “right-wing” or “left-wing”? I mean, in most cases it’s not a sensible question, since there isn’t much theorizing behind the resentment, but in the cases where there is, isn’t it “right-wing”? It’s often been remarked that European Jews were attracted to socialism precisely because it took the focus off them qua Jews.

LikeLike

Many of the comments here concern the vexed question of what is left and right and where to locate parties in political space. There is a decent book on the subject Benoit & Laver Party Policy in Modern Democracies Routledge 2006 which I mention because they have kindly put their data and the book ms online http://www.tcd.ie/Political_Science/ppmd/

One thing they conclude: “our results also suggest quite strongly that the substantive meaning of left and right is a poor international traveler. Tempting as it might be to compare the right in the United States, for example, with the right in Britain (or Russia or Japan) this comparison likely rests on very shaky foundations.”

LikeLike

Reblogged this on aziz isakovic.

LikeLike

Thanks, and welcome to the blog.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pincher Martin writes “The Nazis believed in socialism, but they saw the main villain not as the industrialist or the landlord, but as the successful and enviable Jew”, but economic policy, blunt as it was, was directed at the Jew and the industrialists both as the war dragged on, for obvious reasons. As Timothy Snyder noted in Bloodlands, “Jews were killed because Hitler had defined this as an aim of the war. But even after he made his own desires known, the timing of their death was conditioned by German perceptions of the war’s course and associated economic priorities. Jews were more likely to die when Germans were concerned with food shortages, and less likely to die when Germans were concerned with labor shortages.” 1933 to 1939, it’s about jobs through public works and rearmament, and wages are frozen, unions are banned, and industry nationalized, and yes, always dispossession and later, death, for the Jews. There isn’t much of a class struggle or a liberal bent inherent in the Nazi economic policy so much as simple, overriding control.

LikeLike

Götz Aly’s book is about the Holocaust. Why were the victims Jewish, and

why were the perpetrators German. He doesn’t focus on the details of

fascist ideology. Nor is he interested in placing it on a left-right axis or ever

call the Nazis “left wing”. He doesn’t even lightly touch on German

economic policy during this period. So I’ve streamlined some of his

arguments and added some flourishes here and there.

But Aly’s basic arguments are these:

1) The early Nazis, many of whom would remain leaders in the movement

throughout Hitler’s rule, were mostly aspirational working class German men

who came out of a class that was insecure about their status in the modern economy.

2) As such, the early Nazis were heavily informed by socialist ideas, and

shared with the socialists the equality of Germans as a collective goal, but

they transferred the idea of class struggle to racial struggle. This is not the

same thing as “a fusion of socialist thought and anti-Semitism,” because it

was less philosophical than a historical development.

Here is a good selection from Aly’s on that point:

So the early German socialists recognized these proto-Nazis as fellow

travelers, but they underestimated their sway over them. The socialists assumed that their much finer class analysis would ultimately persuade the anti-Semites that the real problem was not just Jews (who the socialists agreed were a problem), but capitalism itself. They mistook the crudeness of the anti-Semites’ racial beliefs for a lack of conviction, just as you assume the crudeness of the Nazis’ socialist economic policy to be an expression of their true underlying right-wing tendencies.

3) Aly’s most interesting point, one which I’ve never seen highlighted to the

same degree elsewhere, is that German anti-Semitism had a factual basis:

Germans envied Jews because the Jews were in fact more successful. It

wasn’t just that the Jews were different. It certainly wasn’t religious. It was envy. Jews were better in the new economy than were their German neighbors, particularly the Germans who belonged to the class that spawned the Nazis. These Germans were highly conscious of their inferiority and resented it. Envy taken to such a degree does not fit well with any part of the right, traditional or otherwise.

LikeLike

Sorry about the look. I’m not sure how my formatting got so messed up, as I carefully previewed it elsewhere before posting.

LikeLike

Matt — I’m agreeing with you.

No. I take note of the lack of interest in tearing down capitalism in general on the part of Nazis (as opposed to “Jewish domination”). Social Democrats looked at them from the wrong end of the stick, just as you do.

That is just an artefact of a historical contingency by which ethnocentrism was directed downward in England or the United States, where there was little to envy in the minorities. But elsewhere, where you might have large minorities who are more successful than the majority (i.e., Greeks and Armenians in Turkey, for example), it would be absurd to say this reflected “socialistic” tendencies on the part of Turks. Another example is South Africa, where the apartheid system was set up in order to give privileges to the Afrikaners at the expense of the black majority and in relation to the British settlers.

LikeLike

CORRECTION:

LikeLike

PM,

What you’ve done is point to evidence that there was some attempt on the part of German socialists to compete with anti-semites for recruits, and at least one case of a tactical electoral alliance. But that hardly amounts to a case that socialists and anti-semites were on the same side of the ledger in either the ideological or the socio-political/historical sense. A few years ago in the United States, some liberals and leftists argued that the left could draw from the same recruiting pool that Tea Party Republicans were taking from, and/or make tactical alliances on certain issues. These people may have been wrong (they probably were wrong on at least the recruitment issue) but I wouldn’t lump them together with the Tea Party.

The Syriza/ANEL coalition in Greece comes to mind as well.

LikeLike

Envy is a pretty universal human trait, and many successful ethnicities are envied all over the world, but for that envy to be made such a central part in the ideology of a right wing Western political party is unusual if not unique. This was not a matter of granting privileges to some lower-performing majority group. The Nazis identified the Jews as being responsible for most if not all of Germany’s economic ills, and began deliberately and systematically taking everything away from them because of the Nazi belief that the German people would otherwise not have social equality.

Certainly the German socialists of the late nineteenth century didn’t think it was “absurd” to believe that anti-Semitism was simply socialism that had run off the tracks and might be put back on those tracks with a little help.

This begs a question: if those German socialists could look at the proto-Nazis and say, “Yeah, those are fellow socialists,” why is Anglo myopia today sufficient to explain arguments about Nazism’s left wing nature?

LikeLike

Well, there’s no question the Nazis were idiosyncratic. But the idea of a conservatism in which the resentment of a more successful minority played a part is not unique. Traditional French conservatism was anti-Protestant and often anti-Semitic (both Protestants and Jews being more successful in France than the majority).

In Anglo countries, however, the majority and the economic elites were in general considered ethnically or culturally the same.

Maybe it’s similar to how some US conservatives think Hispanics are natural conservatives…

LikeLike

It might be true that “The Nazis identified the Jews as being responsible for most if not all of Germany’s economic ills,” but that’s only because of what the Nazis identified as Germany’s economic ills. They certainly didn’t believe that Germans would have “social equality” in the absence of Jews. Their practice in power abundantly confirms that they had no problem with social and economic inequalities and hierarchies in which the top slots were occupied by virtuous German men. A common thread throughout rightist thought is that unnatural, externally imposed hierarchies are bad, whereas naturally arising hierarchies are good. This shows up even in libertarian thought, where state-supported “crony capitalists” are supposed to be bad, while virtuous independent entrepreneurs are good (a hopeless confusion imo, since market and capitalist institutions are entirely creations of the State, but I digress).

Edmund Burke, Reflections on the Revolution in France

(NB: I don’t think Burke was a proto-Nazi)

LikeLike

This is interesting and relevant – http://www.academia.edu/4736105/Economic_Policy_in_Nazi_Germany_1933-1945

LikeLike

Matt,

You must have missed the opening part of the selection of Aly’s book I quoted in my last post. Here it is again: “Social Democratic leaders saw early on how class ideology could be transformed into racism, but they misinterpreted what was happening. Beginning in the 1880s, they mistook the adherents of anti-Semitic national-socialist movements for believers who had been led astray but who would sooner or later return to the fold and fight for the one true cause.”

To the socialists, the national-socialist parties were from the right classes, said most of the right things about class, and clearly represented groups who were worried about their status in the changing economy – not because they had something like a title or property or fortune or even very often a good stable job to lose, but because they thought the state wouldn’t adequately protect their basic livelihoods as they sought to make their way in the new world. The difference was that the national-socialists focused their ire on the Jew’s economic role, and the socialists thought that anti-Semitism by itself was too crude for serious economic analysis.

The socialists didn’t think there was anything wrong with national-socialists being against Jews, at least successful Jews. The anti-Semitism didn’t bother them. They, too, were against those wealthy Jews. But those Jews would be taken care of when the other capitalists were taken care of.

Pseudoerasmus laughs about Republicans believing Hispanics to be natural conservatives. That’s a pretty good joke in this context. But I was thinking of the German equivalent of Thomas Frank’s What’s the Matter with Kansas? Perhaps What’s the Matter with Hamburg?

The difference is that no one here argues that Nazism was not originally populist. Republicans who think Hispanics are natural conservatives are making clear category errors. Many scholars think Frank is making a much higher caliber of the same mistake.

But those socialists were not making a mistake when they identified national-socialists as being from a class that were ready for the socialist message. How do we know this? Because many of those national-socialist groups, and later the Nazi themselves, would preach a socialist message.

Look, in a span of twelve years the Nazis came to power, crushed domestic opposition, persecuted the Jews, rearmed, went to war against many of their neighbors, and finally murdered all the Jews they could get their hands on.

That’s a pretty busy schedule for any government. So some things were prioritized; others were not. You’ll have to excuse them if what we today think of as their Gini coefficient wasn’t headed in the right direction to properly demonstrate their love for the common German man.

You keep thinking that the Nazis were better political economists than they really were. Do you really think they were that sophisticated? They had crude ideas about how the world worked.

LikeLike

To the socialists, the national-socialist parties were from the right classes, said most of the right things about class, and clearly represented groups who were worried about their status in the changing economy – not because they had something like a title or property or fortune or even very often a good stable job to lose, but because they thought the state wouldn’t adequately protect their basic livelihoods as they sought to make their way in the new world…. those socialists were not making a mistake when they identified national-socialists as being from a class that were ready for the socialist message.

You appear to be shuttling back and forth between the claim that the Nazi leaders were upwardly mobile workers, and the claim that rank-and-file Nazis and Nazi voters were upwardly mobile workers. After all, Thomas Frank’s argument is about rank-and-file Republicans and GOP voters, not the leaders. He’s not saying that GOP politicians are working-class people from humble origins, and that their ideology reflects this. He’s saying lots of ordinary Republicans are and that liberal Democrats should try to do a better job of recruiting them.

Here’s one of your quotes from Aly:

It’s clear that Aly is talking about the leadership, not the rank-and-file. Maybe you have some contrary evidence, but everything I’ve read suggests that the Nazi rank-and-file and electoral base came from largely from the petite-bourgeoisie (although there was a fair amount of support from relatively privileged skilled workers). So, the kind of people most likely to vote for and support the Nazis were people who were not likely to support the socialists. The mass of the industrial working class, on the other hand, was either hostile or indifferent to Nazism, and split between the SPD and the KPD. So, any socialists who thought they could draw from the same electoral pool that the Nazis did were basically wrong.

The socialists didn’t think there was anything wrong with national-socialists being against Jews, at least successful Jews. The anti-Semitism didn’t bother them. They, too, were against those wealthy Jews. But those Jews would be taken care of when the other capitalists were taken care of.

Given the number of German socialists who were Jewish (including Marx himself), this is a pretty implausible interpretation of the statements Aly quotes. Socialists (in theory, at least) did have a problem with Jewish capitalists, but qua capitalists, not qua Jews. They didn’t think (in theory, again) that Jewish capitalists were especially because they were Jews. You think that the difference between socialists and anti-Semites was one of emphasis, when actually two distinct (if overlapping) groups were the target of their respective ire.

You keep thinking that the Nazis were better political economists than they really were. Do you really think they were that sophisticated? They had crude ideas about how the world worked.

Well, they were pretty ruthless guys who almost conquered the world, so yeah, I imagine they tended to have a pretty good idea what they were doing. It’s hard to see how someone could avoid recognizing that crushing trade unions and forcibly lowering wages while keeping private ownership of capital intact will increase capital’s share of income. What is the alternative story supposed to be? That they just thought they were striking a blow for the common man against Jewish Bolshevism and, whoopsie!, the rich got richer? When they purged the genuinely (if perversely) socialist elements in the SA right after they got into power, were they playing some kind of misguided long game against capitalism? It’s already been mentioned that they deliberately embarked on a large-scale privatization program, (the word may have been coined in reference to the Nazi economy), which Bel thinks was done partially to increase political support from wealthy industrialists (pp. 17ff). At some point you just have to start attributing rational intentions to people, even if they’re Nazis.

LikeLike

Matt,

Thomas Frank’s argument was that downscale Republican voters had been hoodwinked into voting against their economic interests because of cultural issues. That’s similar to what Aly claims those nineteenth-century German socialists believed about national-socialist and anti-Semitic voters: Racism and nationalism had waylaid them from the true path of their class interest.

I’ve shuttled back and forth between sociological arguments because Aly shuttles back and forth between sociological arguments in his book. Sometimes he talks about the backgrounds of the early Nazi leaders, and sometimes he talks about the backgrounds of their voters. I would not call either group “upwardly mobile”, however. I prefer the word aspirational. They were hopeful of success, but not assured of it. Aly writes about how many of these Germans were among the first in their families to go to college or enter a trade school because of the expanded educational opportunities provided by the Weimar Republic.

The Nazis drew heavily from this insecure class, particularly after the Depression. These were young people who were among the first in their families to be educated at, say, a polytechnic college, but they still could not find jobs. Their aspirations were crushed. They were angry about it.

Now if you believe that leftist groups can’t make political hay out of the thwarted ambitions of young, angry, semi-educated, jobless people…. well, you’ll have to give me your theories about it some time.

Marx famously wrote about the Jewish question, and the most common interpretation of what he wrote is that it’s anti-Semitic. Marx gave credence to anti-Semitic stereotypes (“Money is the jealous god of Israel, in face of which no other god may exist.”) and then argues the real problem with modern society is that it’s become Judaized, and that Christians and Jews both need to be emancipated from this new secular Judaism.

They were very clear about what they were doing. But that doesn’t make them economically sophisticated.

LikeLike

Again, from Aly’s book:

LikeLike

The combined Socialist & Communist vote in German elections :

1932 = <36%

1930 = <40%

1928 = <41%

1924 = ~35%

There was remarkably little defection out of the left in general. Also consistent was the support for the Catholic Zentrum :

1932 = ~12%

1930 = >12%

1928 = ~12%

1924 = 13.6%

The quasi-separatist Bavarian People’s Party also got about 3% through thick and thin.

In other words, the Nazis went from 2.6% in 1928 to >37% in 1932 by pinching votes from the traditional non-socialist parties other than the Catholic Centre Party.

LikeLike

PE,

I have no answer for those voting stats.

Aly does talk about the preponderance of young people among the Nazis in the 1930s.

But even taking into account changing voter demographics, they don’t come close to explaining most of the change in the level of Nazi support between 1928 and 1932. Four years just isn’t nearly enough time for that kind of shift.

LikeLike

This blogpost got picked up by David Keohane of FT Alphaville.

LikeLike

The book Fascists by Michael Mann investigates in great depth which social strata supported fascism. It wasn’t either marginals or the petit-bourgeoisie (the classic Communist argument) or the industrial working class. It was people associated with the state, employees of the state, the “state class.” Not really surprising that a movement that exalted the state would be supported by people closely connected to the state.

Then, socialist parties had as their core supporters workers in private industry. Now, ironically, today’s left parties have as their core supporters people employed by and closely connected to the state, especially public sector union members. Hence today’s left parties have a similar base of support as the fascists once did.

LikeLike

On page 378, Appendix 4.1 of Mann: public sector employees were 6% of the total NSDAP membership in 1930-32, with a jump to 15% in 1933, which should be interpreted as opportunistic. In reality, “workers” (my guess, rural workers from the East) were the single biggest (though not the majority) category in 1932.

But of the top Nazi leadership (Reichsleiter & Gauleiter level), public employee backgrounds account for 45-50%.

Of course, while socioeconomic background is correlated with ideological orientation, I think the previous partisan affiliation is still the best indicator.

LikeLike

From http://www.amazon.com/Fascists-Michael-Mann/dp/0521538556

Click to enlarge :

LikeLike

Excellent blog. But I have one question. What was the situation of small and medium businesses in Nazi Germany? Is it true that they had a strong oppression. Many libertarians and others argue that small businesses was virtually destroyed. What can you say about this?

LikeLike

Pingback: Right vs Left: Were European fascists left wing? « An Africanist Perspective

I think the tendency to see Nazis as Left-wing among some American Conservative commentators stems in large part from absolutizing the particular historical experience of United States as a country born of a Liberal revolution, and one where there was no Feudalism. This means that an American Conservative wants to “conserve” principles of individualism and personal autonomy, which would be rather alien to the Conservative/Reactionary European tradition represented by de Maistre, de Bonald, Donoso Cortez etc (for the sake of simplicity I am disregarding here the quasi-Feudal, Southern patriarchal tradition of thought in America).

The result is that said American Conservative falls prey to a certain parochialism, where he has trouble wrapping his head around the fact that Conservatism can very well be Statist and Collectivist, in places where Statism and Collectivism are fully compatibile with the postulated “Tradition” of the national community in question.

To the point of whether Nazis stood against Capitalism qua Capitalism or only the “Jewish” parts: Gottfired Feder made the distinction between “exploitative Capital” (raffende Kapital) and “productive Capital” (schaffende Kapital), which strongly suggests that they had no problem the Capitalism as an economic principle in itself.

LikeLike

no problem with Capitalism

LikeLike

“I think the tendency to see Nazis as Left-wing among some American Conservative commentators stems in large part from…” the effort of American Conservatives to tar the left with whatever brush and tar is available (and not so much from consideration of the sociology and economy of 1930ies Germany).

LikeLike

wonderful blog ,post and comments.

I have modestly given this some publicity down under.

Keep it up

LikeLike

Thank you for being one of the few bloggers who openly says the bloody obvious, namely, “The common thread to the right in history is not laissez-faire, but the tendency to support business or property. The common thread to the left is to redistribute income and property.”

It can be stated more simply: the right-wing supports the maintenance of established wealth and power elites by whatever means necessary, and the left-wing supports the redistribution of wealth and power to the poor and powerless. This is why the left wing supports democracy and the right wing supports monarchy. The origin of the terms “left-wing” and “right-wing” was in revolutionary France, and they refered to the democratic party and the monarchist party respectively.

There is a wrinkle in that some political groups are currently out of power but wish to become the new wealth and power elites. These groups are on the whole right-wing, but may be at odds with the existing wealth and power elite — temporarily. Therefore they pose as left-wingers until they get into power, at which point they reveal their true right-wing character. (Genuine left-wingers wish to “flatten” wealth and do NOT want to become a new elite.)

LikeLike

Examples of right-wingers who pretended to be left-wingers until they got into power include Napoleon (after taking over the Republic he promptly reestablished titles of nobility and gave them to his family and friends) and of course Hitler. It’s a common thing.

LikeLike

I see you don’t monetize your website, don’t waste your

traffic, you can earn additional cash every month because you’ve got hi quality content.

If you want to know how to make extra bucks, search for: Mertiso’s

tips best adsense alternative

LikeLike

Pingback: IL PEGGIOR PRODOTTO DEL FANELLISMO E’ STATO L’ANTIFANELLISMO (semicit.) | La Voce della Verità

Lol ignoring Nazis nationlizing hundreds of firms

LikeLike

Comparing per capita GDP growth with real wage growth is comparing apples and pears. GDP per capita is not deflated, real wages are deflated, I assume, with the CPI. The best thing to do would be to deflate both variables. Although deflating the variables with their specific deflator is not a good way, since the CPI estimates more inflation and, therefore, when correcting the series, wages are discounted more.

LikeLike

Pingback: Nightcap | Notes On Liberty

Pingback: Απαντώντας σε 5 μύθους γύρω απ’ τον φασισμό: 1. Ήταν οι Ναζί «σοσιαλιστές»; | ΝΕα Διεθνιστική Αριστερά