An elaboration on Ricardo Hausmann’s article “The Education Myth” arguing that education is an overrated tool of economic development. This post also responds to a criticism of Hausmann’s views which appeared at the Spanish group blog Politikon; and also discusses whether developing countries really can raise scores on achievement tests.

[Edit: This blogpost has now been translated into Spanish as “El romanticismo educativo y el desarrollo económico“.]

The Harvard economist Ricardo Hausmann recently published a column in Project Syndicate called “The Education Myth“, arguing that education has been an overrated tool of economic development. His target is what he calls the “education, education, education” crowd, the sort you can find at Davos and other places where much bullshit is intoned with great piety. But I think his argument contains a valuable insight about the ability of developing countries to actually improve educational outcomes.

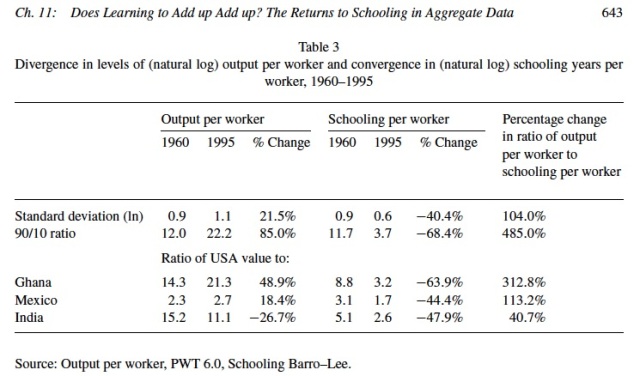

Hausmann’s primary observation is this: those countries which tripled their average years of schooling from 2.8 years to 8.3 years between 1960 and 2010 only managed to increase their GDP per worker by 167%. He cites Pritchett 2001, but I think a more interesting summary is found in Pritchett’s chapter 11 in The Handbook of the Economics of Education (Vol. 1) :

During those 35 years, the world’s standard deviation of GDP per worker increased, while the standard deviation of schooling per worker declined. The inequality between the 90th percentile amongst countries in GDP per worker and the bottom 10% nearly doubled, even as the 90/10 ratio of schooling per worker improved dramatically. If education is so important for development, this is a puzzle indeed.

Of course simply comparing schooling and growth rates is a crude correlational argument which omits the many other determinants of growth. But Hausmann is simplifying things for a popular audience in order to convey a solid finding from the empirical literature in economic growth: the variable “years of schooling” by itself has a low explanatory power for growth rates in GDP per worker whether in cross-country regressions that include standard controls, or in growth accounting which attempts to directly measure the contribution of human capital to the growth rates of individual countries.

Pritchett 2001 cannot find significant social returns to schooling in most developing countries — not much detectable impact above and beyond the sum of private returns to schooling. This is even though, within countries, those with more schooling still tend to have higher incomes. The table below for Africa is from Barro-Lee:

The above summarises the results of growth accounting — counting the inputs that go into the production process (labour, capital, educational capital) and comparing them with output. The unexplained or residual term (TFP) is conventionally interpreted as the growth in the efficiency with which the inputs are used to generate output.

What the above shows for Sub-Saharan Africa is that even as the contribution from educational investment was soaring, capital contribution and TFP were collapsing in the 1970s-90s. The associations here are not necessarily causal. But if they are causal, it could imply that the educated were doing socially useless things, such as taking bribes as functionaries in the customs bureau in exchange for import licences. If the associations are not causal, then it could imply that the supply of educated people was rising even as the demand for them was not growing fast enough. Or it could be a little of both.

Another possibility is that all these years of schooling were hollow, i.e., they implied no real learning nor any skill acquisition. Pritchett presents limited evidence this cannot be completely true, e.g., the fertility of women with more schooling declined. Evidence from Barro-Lee (also see their VoxEU article) also make that idea unlikely.

However, labour & education economist Eric Hanushek is quite blunt about it: despite large global increases in rates of school enrolment and in average years of school attendence, the “best available evidence shows that many of the students appeared not to learn anything” [emphasis mine]. This view is based on the very low test scores from developing countries in international assessments :

[Source: Hanushek & Woessman, The Knowledge Capital of Nations: Education and the Economics of Growth. The means don’t convey the full impression: see the distribution of scores, with 400 defined as “functionally illiterate”.]

[Source: Hanushek & Woessman, The Knowledge Capital of Nations: Education and the Economics of Growth. The means don’t convey the full impression: see the distribution of scores, with 400 defined as “functionally illiterate”.]

So what’s the best way to interpret Hausmann’s article ?

- Yes, “years of schooling” is a poor proxy for educational outcomes. But it captures very well the policy instrument that governments can actually control easily — building large boxes and herding children into them like cattle. That investment has obviously not caused a convergence in test scores between developed and developing countries.

- There’s no evidence that education, how ever measured, promotes the sort of growth rates that result in eventual convergence with the rich countries.

- Nonetheless, there’s evidence to suggest education has contributed to the positive but relatively low growth rates which have been insufficient for convergence. Economic growth research implicitly assumes that the rapid convergence of East Asia with the western countries is ‘normal’ and the slow growth of other non-western countries ‘abnormal’. But maybe the former is the anomaly.

§ § §

At the Spanish group blog Politikon, Roger Senserrich largely agreed with Hausmann. But two other Politikons, Octavio Medina and Lucas Gortázar, took exception to the Hausmann-Senserrich view. (They were apparently trolling one another for fun.)

The main objection of Medina and Gortázar, both of whom are affiliated with the World Bank, is that “years of schooling” is a bad proxy for education, so the quality of education, instead of measures of school access, is now being used to study the relationship between economic growth and education. “What a child learns in his first year of primary school is not the same in Kenya as what a child learns in Finland or Uruguay”. Then Medina and Gortázar present a plot very similar to the one below in order to argue, yes, indeed, there is an important relationship between economic growth and the “quality of education”:

[Source: the OECD publication “Universal Basic Skills” by Hanushek & Woessmann]

[Source: the OECD publication “Universal Basic Skills” by Hanushek & Woessmann]

Unfortunately the Medina-Gortázar argument is also based on a bad proxy. Scores on PISA and TIMSS are not — I repeat, not — proxies for “educational quality”. They reflect student outcomes. Institutional input variables, like “teacher quality” or “school quality”, should not be conflated with student output variables. Hanushek and Woessmann consistently use test scores as a proxy for (their own words) cognitive skills. From the same OECD publication:

The focus on cognitive skills has a number of potential advantages. First, it captures variations in the knowledge and ability that schools strive to produce, and thus relates the putative outputs of schooling to subsequent economic success. Second, by emphasising total outcomes of education, it incorporates skills from any source – including families and innate ability as well as schools. Third, by allowing for differences in performance among students whose schooling differs in quality (but possibly not in quantity), it acknowledges – and invites investigation of – the effect of different policies on school quality. [pg 89]

So just how optimistic should we be about developing countries’ ability to improve test scores ? We do know poor countries have raised them, e.g., Brazil’s PISA score has gone up by about one-half standard deviation in the past decade. Rather it’s a question of whether the gap can be closed between developed and developing countries, i.e., Brazil’s is still more than a standard deviation below the OECD average which puts the country’s mean below the “functionally literate” category.

There’s a chain of causes that need to be addressed. We must know what achievement tests measure; whether ‘optimal’ schools can raise test scores to growth-accelerating levels; and what are the prospects for moving bad schools in developing countries closer to ‘optimal’ ones.

§ § §

Although tests like PISA or TIMSS measure learning, they also implicitly and indirectly measure the ability to learn. Which is why these tests, along with the American SATs, are strongly correlated with IQ. (See Rindermann 2007 for the high correlations in country means; and Frey & Detterman 2004 for the individual-level correlation for the American SATs.)

I assume that in developing countries (1) cognitive ability is quite malleable because the poor environmental conditions lead to childhood stunting and cognitive impairment; and (2) the relationship between cognitive ability and achievement test scores is imperfect enough for wiggle-room.

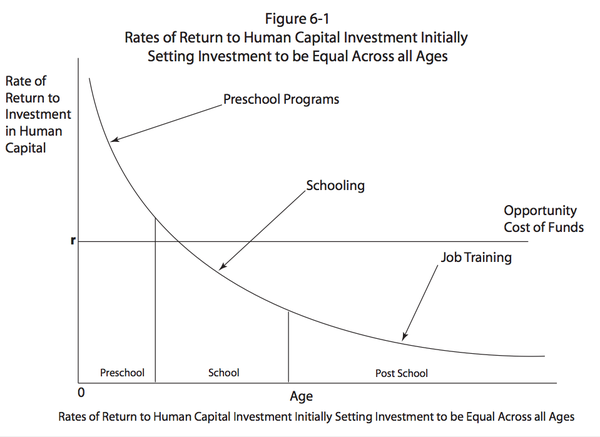

But those researchers who believe achievement test scores can be raised (in developed countries) usually stress the importance of very early childhood intervention. James Heckman, Nobel laureate and celebrated critic of The Bell Curve, presents the most informed case for optimism. Yet even he argues that the window for intervention in improving academic achievement (and other life outcomes) is substantially prior to conventional formal schooling. From Heckman :

Gaps in the capabilities that play important roles in determining diverse adult outcomes open up early across socioeconomic groups. The gaps originate before formal schooling begins and persist through childhood and into adulthood. Remediating the problems created by the gaps is not as cost effective as preventing them at the outset.

For example, schooling after the second grade plays only a minor role in creating or reducing gaps. Conventional measures of educational inputs — class size and teacher salaries — that receive so much attention in policy debates have small effects on creating or eliminating disparities. This is surprising when one thinks of the great inequality in schooling quality across the United States and especially among disadvantaged communities.

My colleagues and I have looked at this. We controlled for the effects of early family environments using conventional statistical models. The gaps substantially narrowed. This is consistent with evidence in the Coleman Report (which was published in 1966) that showed family characteristics, not those of schools, explain much of the variability in student test scores across schools.

[Edit: This is how Carneiro & Heckman visualise it.]

Heckman argues improving family environments and implementing very early preschool programmes for infants (!!!) is the most cost-effective way to raise outcomes. These are things which developed countries even with their strong institutions can barely do, if at all. Imagine that for developing countries, many of whom barely manage universal school enrolment.

§ § §

But I’m willing to believe developing countries have more room for improving test scores through better schools. That’s because having ‘schools’ on paper does not necessarily imply that even rudimentary education is taking place. Especially in some of the poorest countries, the problems with school quality often include the regular attendance of teachers, missing textbooks, or sometimes even no ceilings !

How to improve school quality in the first place, though ? Although I’m quite sceptical that middle-income countries would benefit from more spending per student, surely Afghanistan or Burundi could.

Glewwe et al. (2013) reviews studies between 1990 and 2010 about the impact of a variety of educational inputs on measures of student learning (such as test scores) in developing countries:

[The difference between the second and third columns (36) refer to studies containing OLS using only cross-sectional data which, according to the authors, did not adequately deal with omitted variables, endogeneity, self-selection, etc. etc.]

The inconclusive effect of even basic infrastructural inputs like textbooks is surprising. On the other hand, maybe there’s some hope from lowering the pupil-teacher ratio, and the impact of teacher absenteeism hasn’t been studied very much. But as the authors put it, “perhaps the most useful conclusion to draw for policy is that there is little empirical support for a wide variety of school and teacher characteristics that some observers may view as priorities for school spending”.

Of course there’s been an explosion of randomised controlled trials and experimental studies from developing countries in the last 10 years, so there will be much more evidence to come. But when I read about the collapse of a financial incentive experiment to reduce absenteeism by nurses (ungated) at Indian hospitals, I’m not terribly optimistic about the vast institutional changes that appear necessary to improve the quality of schools.

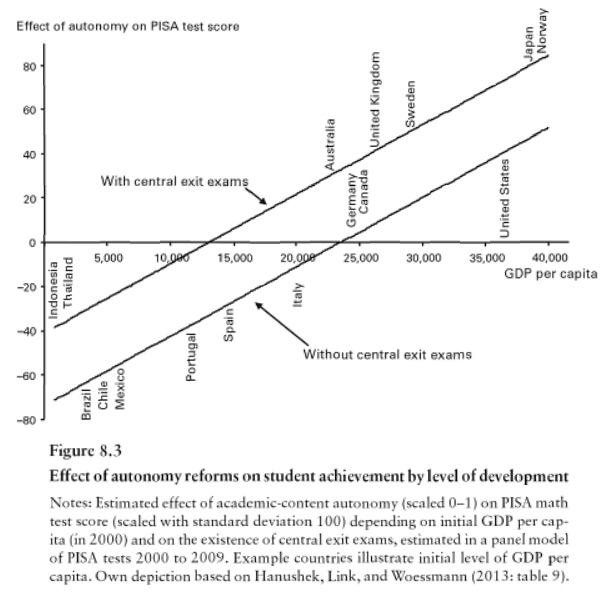

What is Hanushek’s advice to developing countries ? It’s mostly the fads that now animate the educational circles in the United States and some other developed countries:

- get smarter teachers (and test them)

- track students

- use school leaving exams

- decentralisation of educational decision-making

Hanushek actually argues “school choice”, by itself, is a bad idea in developing countries and could worsen student outcomes. So he prefers those reforms in combination, and his optimism is reflected in projections like this based on cross-country correlations with samples of 50 or whatever:

Well, Nepal and El Salvador, problem solved !

§ § §

Although the returns to improving school quality (with enrolment held constant) would be higher than increasing enrolment (with quality held constant), the latter seems the more realistic option for most developing countries. After all, the very rich and manageably sized Qatar can’t manage a PISA score of 400 ! And there’s still a lot of room left for raising percentage enrolled and years of schooling :

We’ve come full circle. Things started with Hausmann’s observation that increasing access to schools per se hasn’t done very much. But despite the low productivity of schools and the high likelihood of diminishing returns to more inputs, maybe eliminating the educational ‘slack’ is still the low-hanging fruit for most developing countries.

Postscript: I posted a quick remark about causal identification regarding the relationship between test scores and economic growth in the first comment of the comments section.

NOTE: Much of the literature assumes that bad schools are one of the fundamental causes of low achievement. When there are missing teachers, ceilings, and textbooks, that may be a reasonable assumption for developing countries. But what’s the evidence ? The question of how much the relationship between achievement test scores and economic growth is driven specifically by school quality, as opposed to non-school determinants of achievement test scores, is addressed in Hanushek & Woessmann 2012 (especially in section 5, ungated version). The correlations between growth rates and institutional measures of schooling (external exit exam systems, the share of privately operated schools, the centralisation of decision-making, etc., which are taken to be exogenous) are compared with the correlations between achievement tests and growth rates. But I think most of these institutional measures themselves must be strongly correlated with both cognitive ability and political/economic institutions. The authors insist the schooling effects survive after citing all kinds of literature, but the sample sizes are smallish, and I can’t tell from what they say whether the findings also really apply to developing countries without looking at other papers they cite.

LikeLike

I can’t help the feeling that all these studies are just correlating different indicators of the S factor with each other and finding positive relationships. Sometimes they control for a third indicator and still get some positive relationship. All of these findings are expected on the basis of the general factor alone and consistent with non-causal correlations. Change my mind.

LikeLike

First, this is an great post.

Despite the detailed and necessary discussion of pure educational outcomes in the second half of the article, it’s the first half, detailing the anti-contribution of education to convergence, that seems to require a theory. I certainly don’t have one of my own – and very different theories might be in order countries as diverse as Ghana, Mexico, and India. Bob Allen, in his “Global Economic History” (2011), mentions education as a critical component for both “standard” (USA, Germany) and “Big Push” (USSR, Japan) convergence strategies. But he also relates low wage rates to slow economic growth – especially in the absence of a well-directed growth program. Cheap labor only requires good-enough technology; it doesn’t require the kind of technology that can only deployed into an educated workforce. The kind of positive-but-not-enough-to-converge output growth per worker that, say, Ghana experienced up until 1995 would be illustrative of this later dynamic.

But India presents an interesting case – and here one wishes that we had another, 21st century cut on the data. When i was a teenager in the 1960’s, the only Indian export that I knew was Madras cotton. By the mid 1990’s, I was making a living off India’s massive “export” of technically trained workers. Despite falling educational attainment per capita, India was clearly investing massively in education even though it was not yet able to absorb the output of its university system. Not all that output was high quality (Pankaj Mishra describes in bitter detail his worthless non-technical education at a provincial Indian university), but it was good enough to help sustain a fast growing high tech industry in the US. A lot has happened since then and I would like to see how that plays out in a format like Pritchett’s “Table 3”. India (I presume) absorbs more of its educational output now, but is that a top 10% development or has it made an impact on the overall numbers?

LikeLike

Pingback: Romanticismo educativo y desarrollo económico | Katalepsis

“get smarter teachers (and test them)

track students

use school leaving exams

decentralisation of educational decision-making”

That’s the system I went through half a century ago. It seems that it’s time for the developed world, or parts of it, to rediscover the strengths of its traditions, and bin the impositions of the Forces of Progress over recent decades.

LikeLike

Sure but the question has to do with closing the test score gap between developed & developing countries. those good-old-fashioned methods won’t do it.

LikeLike

“the question has to do with closing the test score gap between developed & developing countries”: you raised two questions in your opening para – the first was whether education is an overrated tool of economic development. If it is sufficiently overrated then the second question, about the results of achievement tests, may not matter much.

“I don’t want to get into the question of the malleability of cognitive ability, so I will simply assume that in developing countries (1) it is more malleable because of the much greater environmental variation”: if so, it might be far more cost-effective to attend to questions of nutrition and disease

than questions of styles, or length, of schooling.

LikeLike

(1) Actually achievement tests do matter, but I don’t believe they can be raised very much. (2) nutrition & disease is in part 2 (if those Spaniards reply to me) But the evidence on the impact of malnutrition & disease on cognitive ability is not plentiful.

LikeLike

Lauren Willis cites research in her 2012 paper on Financial Education: What have we Learned so Far?: “At the input stage, rather than attempting to increase financial literacy, we might focus on increasing the numeracy levels of consumers through math education and prenatal interventions. Although increasing numeracy might be achieved by the math instruction component of financial education programs, better math programs in the public schools could be more efficacious. Math ability is lower for those with very low birth weight (Taylor, Espy, and Anderson 2009) or in-utero alcohol exposure (Rasmussen and Bisanz 2009). Programs targeted at improv¬ing fetal brain development might be more effective in increasing numeracy and improving financial behavior than financial education.” http://www.cfapubs.org/doi/pdf/10.2470/rf.v2012.n3.10

LikeLike

Tell me, “developing countries”. How many actually have “developed” over, say, the past forty years? Which? Which part of the world are they in? What I’m driving at is to ask to what extent “developing” is just a euphemism, and to what extent it can be taken literally.

LikeLike

Polynucleotides.

LikeLike

The more I look at problems like this, the more I feel that collecting good data (and understanding how inaccurate it is) is hard, and analyzing it rigorously to learn things about a messy world is even harder. But public policy is important enough to spend a lot of effort on getting it right, and avoiding statistical arguments has its own problems.

LikeLike

“best available evidence shows that many of the students appeared not to learn anything” indeed.

Years spent studying is not a good indicator of education level once quality of schooling varies greatly, but the ultimate differentiator when it comes to development is the set of institutions individuals “operate”. Look at China, its population is getting better education over the years but reforms to its productive system dictated its improvement in well-being. On the other hand, Cuban government loves to tell how low are their levels of illiteracy but Cuba is going nowhere until they change course radically.

For development, more important than schools is a set of institutions that make school a valid bet on finding prosperity not just a number for government show off.

LikeLike

Pingback: On the effects of inequality on economic growth | Nintil